-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

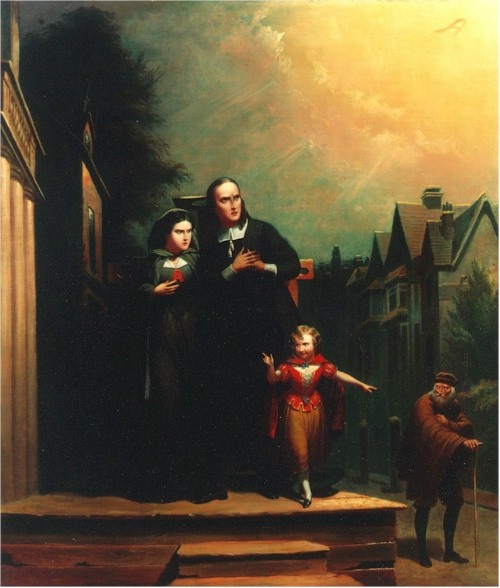

The Scarlet Letter

I recently met up with the people of CardiffRead; a nice bunch of people who meet up once a month to chat about a book they've all read. I haven't read a book because I ought to for some time, so the experience was strange, but I relished the opportunity to discuss The Scarlet Letter with them, and was then asked to write a short piece to summarise my thoughts. I know 600 words might not do the piece justice, but here are a few ideas that were raised as I read.

nb. The page numbers I reference correspond to the Oxford World's Classics edition

Nathaniel Hawthorne�s The Scarlet Letter explores the contrast between what we appear to be and what we truely are, and how these elements are dictated to by various means, and whether it is ever possible to present a true image of ourselves.

It is a historical document dealing with two fictions; that of the reader experiencing Hawthorne�s context as a writer in the 19th Century; and that of the reader experiencing Hawthorne�s tale of his 17th Century Puritan ancestors, and his attempts at understanding, and perhaps atoning, for their acts. The Scarlet Letter deals with the intersection of these two elements; a story about the past is narrated in the past tense, while we are often reminded that we are located in Hawthorne�s present; he describes �a boldness and rotundity of speech among these matrons, as most of them seemed to be, that would startle us at the present day...� (page 42). Thus we view the series of events through two layers of context, and are constantly having to question the information provided. Hawthorne appears to be a well-meaning romance writer; this may not be not so, as he litters his text with linguistic complexities and historical anomalies. Hawthorne was well read in his Puritan history, though throughout the text historical people and fact meet the fictional. Instead, Hawthorne seems to encourage the reader to realise the difficulties of representation; the scarlet letter, with its inifinitude of linguistic and symbolic meaning, is the perfect image for his concept.

The scarlet letter obviously holds a multitude of meanings for the characters, the author and the reader, but it is the symbol�s potential to mean which affects the text significantly, and we must witness and evaluate the changing status of this �token�; we may wish to speculate whether the �A� stands for �adulteror�, �angel�, �able�, but what is more appropriate to consider is the transformative effect each interpretation provides.

The fluid and transitional translation of the letter by the Puritan community, as act of punishment and as symbolic meaning, seemingly highlights Hawthorne�s contempt of this rigid social structure, and he illustrates this opinion further by contrasting the culture against nature.

Dimmesdale is prevented by his cultural norms from revealing his truth; �the daylight of this world shall not see our meeting� (page 121); but may liaise and converse candidly with Hester in the forest; �Happy are you, Hester, that wear the scarlet letter openly upon your bosom! Mine burns in secret!� (page 150). It is within nature that the characters may ignore their Puritan bindings. Hester literally discards the scarlet letter.

It is within nature that Pearl exists; her paternal identity withheld, she is cast into an �ethical wilderness� (Cindy Weinstein, 2007), unable to be accepted by the community. She is further dehumanised by Hester�s �creat[ing] an analogy between the object of her affection, and the emblem of her guilt and torture� (page 80). Pearl becomes a signifier to Hester, who, choosing to accept the scarlet letter only as a punishment, turns her into an �imp of evil� (page 74).

It is only by escaping the confines of the community that Pearl is able to establish herself as a person. Hawthorne finally reveals the conclusion of one of the main concerns of the narrative; whether Pearl�s paternal identity will be announced. We have to wonder, given the information provided, whether it was relevant at all, and this serves Hawthorne�s agenda; to scrutinise Puritan concerns and their impact. Hawthorne represents duplicity through his characters, all of whom must hold two concepts to be true at once; the priest who has sinned; the community who shuns while asking for favours; the punished who returns to the punisher.

No matter how Hawthorne may question Hester�s acts and intentions, choices and opinions, she remains the heroine of the story. She may be a paradigm of stoicism. She may be a feminist blueprint. Much like the author�s eyes �would not be turned aside� (page 27) from his discovery in the Custom House, neither may ours from Hester Prynne.

8:34 p.m. - 2011-08-13

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

|